The organisers of the 66th IEEE Symposium On Foundations Of Computer Science (FOCS) 2025 asked me to construct a cryptic crossword for the event.

Here it is. Enjoy.

EATCS Council 2025 Election Statement

I am delighted to be nominated for the EATCS Council. I have completed two full terms but would be honoured to stay on board for another round. You can see my previous statements below; most of the opinions there remain valid today, in particular with respect to publication models for TCS, the connection between TCS and the Sciences, and my stance on core principles of scientific inquiry.

ICALP

Looking back at earlier statements, they are dominated by my ambition to increase the quality of ICALP, primarily by giving ICALP a steering committee. I have served in that steering committee for a while now, and currently am trusted with steering it. I think this has turned out extremely well. However, I have become convinced that it is important that the ICALP steering committee remains grounded in the wider concerns of EATCS and will continue to try to align expectations in both directions.

Fundamental TCS Ph.D. Course

From the time when I was a Ph.D. student, TCS has evolved dramatically in many directions. Students are recruited from many different institutions, and at the same time, academic institutions have become increasingly specialised. As a consequence many young researchers lack a common core of TCS knowledge, simply because few institutions have the resources to offer a full palette of graduate courses.

I would like EATCS to take responsibility for the “comprehensive view of TCS” and organise a regular (say, yearly) TCS core curriculum Ph.D. course; preferably as a one-week intensive course, with a relatively stable curriculum each year. This is not a “topics” course, nor a “recent advances” course, but the “graduate-level _foundations_ of theory of computation”. Also, it would be a great place to meet fellow young students.

To set this up stably—and make sure it happens more than once and doesn’t deteriorate into “whatever famous professor X thinks is cool this week”-course—I think we need a steering committee or an advisory board. But I haven’t thought this through; EATCS would be the right forum to host these ideas.

The Open Society and Its Digital Enemies I: Knowledge (Lex conference on trustworthy knowledge, Copenhagen 2025)

On 23 April 2025 I had the privilege of speaking at the conference Trustworthy Knowledge in the AI Age, organised by the lex.dk, the organisation behind the Danish National Encyclopaedia. (I serve on the Scientific Advisory Board of that organisation.)

- Conference web page, with links to all presentations: Konference: Troværdig viden i AI-tidsalderen.

- Direct link to my presentation: Lex konference 2025: Thore Husfeldt – Det åbne samfund og dets digitale fjender

Both professionally and privately I spend a lot of time thinking about these issues – information, knowledge, trust, and (artificial) intelligence, etc. – more than what can be usefully covered in the 12 minute time slot given by the conference format. As a challenge to myself I decided to frame my presentation using concepts developed by Karl Popper and David Deutsch, basically in the former’s essay

Popper, Karl R. (1962). On the Sources of Knowledge and of Ignorance. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 23 (2):292-293.

English summary

Lightly edited of Youtube’s automatic captioning (in Danish) auto-translated into English.

This year, I’ve taken on a rhetorical task: to frame my thoughts about the digital society and the relationship between computation and technology within Karl Popper’s famous work The Open Society and Its Enemies. There are at least nine chapters I could talk about (censorship, surveillance, democr, but today I’ll focus only on one: knowledge.

So, this will be an introduction to Popper’s concept of knowledge—or his epistemology, to use a fancy word—filtered through my own views. It’s more opinionated than I usually allow myself to be in public talks..

Let’s start with a crash course on networking, internet architecture, and the Internet Protocol (IP).

On your left, we see Ane, the sender. She wonders: What is trustworthy knowledge? And she wants to ask Mads, the recipient, that question. She uses the internet. The IP protocol first breaks Ane’s question into several smaller packets—let’s say four. These packets are then sent through the digital infrastructure: cables, routers, antennas, towers, and so on.

Mads is on a train with a mobile phone. The train is moving. These packets take different paths at different speeds. Some are lost, some are altered, but they finally arrive at Mads. The IP protocol ensures this delivery, and it has done so since 1981—before satellite communication, before mobile phones. It has worked for over a generation and ensures digital infrastructure does what it should.

Now, what does a packet contain? Beside the actual message fragment (the “payload”) It contains so-called metadata—or “control” data. At the bottom, you can see the sender and receiver addresses. A cell tower or satellite sees the recipient and sends the packet in the right direction, hoping some other part of the infrastructure forwards it.

That ends the technical part of this lecture. So now, after that much heavy information, it’s time for a joke. On April 1st, 2003, a member of the working group that defines these protocols proposed including the “evil bit” in the protocol metadata. Since there was some extra space in these packets, the idea was to mark packets containing evil information—hack tools, malware, etc. The internet could then prevent their transmission.

If the bit is set to zero, the packet has no evil intent. If set to one, it does.

This is a joke. It’s an April Fools’ prank. Still, it reflects our moral intuition: wouldn’t it be nice if the internet could tell us what information is good or bad, safe or unsafe, trustworthy or not?

My aim is to convince you that this is the wrong question. It is an epistemologically uninformed question with no good answer. Mind you, it’s psychologically hard for us to accept that it’s the wrong question—because it feels like a good one. I feel it too. But asking the question is like falling for the April Fool’s joke.

To illustrate that bad questions can lead us astray, let’s consider another example from biology: What is the purpose of biodiversity? Many smart people thought hard about this for 2000 years—Lamarck, Aristotle—and came to the wrong conclusions.

Why? Because it was the wrong question. Darwin’s insight was that there is no plan, no purpose, no “good species”. Instead, today we know how to ask: what is the mechanism? And the answer is: mutation and selection. Or in Popper’s philosophy: conjecture and refutation. So again: smart people spent centuries on the wrong question until someone asked the right one—and that changed our understanding of biology for the better.

Similarly, in Popper’s The Open Society (1944), he addresses another famous wrong question: Who should rule?

This question had occupied moral thinkers for 2000 years: their answer included the wise philosopher-king, various gods, the proletariat, the sans-culottes, priests, the intellectuals. All these answers were wrong, for the same reason: it’s the wrong question.

Popper’s key insight is that this question leads to tyranny. If someone has unique authority to rule, then protecting that authority becomes virtuous, and criticism therefore becomes immoral. The right question is instead: How can we remove bad rulers? Because mistakes are inevitable, and we need mechanisms to replace those in power.

The answers? Freedom of speech and free elections. That’s the foundation of the open society.

Now, applying this to knowledge: What is the foundation of knowledge?—is also the wrong question. People have tried to answer this for millennia. Plato said knowledge is justified and true belief. Rationalists said it’s based on reason. Empiricists said it’s based on experience. And so on. All of these answers are in conflict with each other. And again, Popper says: they’re all wrong, because the question is wrong.

For knowledge is not based on anything. Instead, knowledge is a guess that has survived criticism. It’s the best explanation we currently have—until it’s refuted.

So: guesses-and-criticism, hypotheses-and-falsification, mutation-and-selection—it’s all the same idea. And tt’s a very practical philosophy, and it tells us what to do: we need the open society to find correct information, just like we democracy to replace bad leaders.

Let me summarise: many traditional views of knowledge—like Plato’s or those of rationalists and empiricists—are not just wrong but wrong for the same reason: they assume knowledge must have a foundation.

Popper’s view is that knowledge is not grounded in anything. It is provisional, yet objective.

The two sides are fundamentally opposed:

- One side says: true knowledge must be protected from misinformation.

- Popper’s side says: true knowledge must be exposed to criticism.

These lead to very different practical conclusions for how to build an information society.

So let’s return to the internet protocol. If you paid attention during slide 2, you saw some packets were lost or altered. Mads notices he’s missing the third packet and that the fourth may be corrupted. He sends two messages back: “I didn’t get packet three, and I don’t trust packet four—can you resend them?”

Ane resends them. This happens all the time during internet transfer, whenever you send a message. Even now, for those watching this talk online. Packet loss, message corruption, and error correction are constant and happen in milliseconds. They’re part of the internet protocol.

The essential metadata of IP therefore isn’t just the sender and receiver addresses—we’ve been used to those from paper-based postal services. Instead, equally important are the error detection mechanisms.

Thus, error detection correction is indispensable part of the protocol, while the “evil bit” is a joke. If you understand that distinction, I have succeeded in this talk.

To summarize:

There are two opposing conclusions about trustworthiness and information:

- The traditional view says trustworthy information is based on good arguments and must be protected.

- The Popperian view—which I believe—is that trustworthy information is what has withstood criticism. It’s defined by the absence of counterarguments, not the presence of supporting evidence.

So the ethical obligation becomes: We must preserve methods of error detection.

Gadfather, Gay Unlocked in Secret Sartre

For immediate release. To the excitement of board gamers and academics all over the world, the array of playable characters in Secret Sartre—the social deduction game of academic intrigue and ideological infighting—has been extended with the 2023 president of Harvard University Dr. Claudine Gay and economics professor Gad Saad from Concordia University.

“When we released Secret Sartre in 2015, what we then saw as the intellectual and moral corruption of Western Academia was still a contentious issue. By 2023, this position has entered the mainstream Overton window of acceptable discourse,” says Thore Husfeldt, who considers himself the designer of Secret Sartre “at least in the postmodern sense”.

Sartre is a reskinning of the incredibly well-made and highly playable Secret Hitler (Temkin et al., 2016), moving the original’s setting and theme from the 1930’s German Reichstag to faculty politics at a modern university. In Hitler, the ideological fault line is between liberals and fascists, in Sartre, it is between the Enlightenment and Postmodernism.

“It is immensely gratifying that a small decade after both games were released, the themes have come full circle,” opines Husfeldt, ”and a wider public now realises that the progressive ideology—call it postmodernism, collectivism, DEI, woke, critical social justice, neo-marxism—is not only illiberal, but openly antisemitic. By now, you could play Secret Sartre with the allegiance cards of the original just as well!”

To commemorate the developments in the 4th quarter of 2023, the rosters of both factions are extended by two of the most respected intellectuals of either side: Team Postmodernism is bolstered by Dr. Claudine Gay, the 2023 President of Harvard University, to represent the moral authority and intellectual and academic standards of one of our most trusted institutions. To balance this, the brave members of Team Enlightenment now have access to the Gadfather Himself, author of the The Parasitic Mind.

Earlier Expansions

This is the third character expansion to Secret Sarte, known among gamers as the “Harvard expansion”.

- Original 2015 release of Secret Sartre: Postmodernism: Derrida, Foucault, Rorty, Sartre. Enlightenment: Dennet, Curie, Darwin, Russel, Chomsky, Dawkins.

- 2017 Evergreen State College expansion: Enlightenment: JB Peterson, B Weinstein.

- 2020 Critical Theory expansion: Postmodernism: Marcuse, Horkheimer. Enlightenment: Pluckrose, Lindsay.

References

The art o the Saad card is based on a photo by Gage Skidmore, released at Wikimedia Commons under CC-BY 2.0. The art on the Gay card is just something I found somewhere and use without attribution.

2023-24 Appearances about Generative AI in Higher Education

Incomplete overview of public and semi-public presentations and converstations I’ve held about generative artificial intelligence and education in early 2023. Some of these are recorded; enjoy!

Digitisation, Generative AI, and Higher Education. 17 January 2023. Presentation at Semester Workshop for Education, CS Department, IT University of Copenhagen.

Digitisation, Generative AI, and Higher Education. 1 March 2023. Presentation at Department for Digital Design, IT University of Copenhagen.

Digitalisering, generativ AI och högre utbildning (in Swedish). 2 March 2023. Presentation and panel debate at seminar Artificiell intelligens och den högre utbildningens framtid, Chalmers AI Research Centre “Chair”, Gothenburg, Sweden. [Video part I], , [blog entry of Häggström].

Digitisation, Generative AI, and Higher Education. 7 March 2023. Presentation at Department for Business Informatics, IT University of Copenhagen.

Digitisation, Generative AI, and Higher Education, 17 March 2023, recorded lecture for https://www.teknosofikum.dk

Digitalisering, generativ ki og højere uddannelse (in Danish), 23 March 2023, presentation of Danish business leader group VL gruppe 77.

GPT: Higher Education’s Jurassic Park Moment?, 2 April 2023, episode 105 of John Danaher’s podcast Philosophical Disquisitions. [2h audio podcast]

Generativ ki i højere uddannelse (in Danish). 12 April 2023, presentation at conference “Konference om digital informationssøgning og betydningen af ChatGPT”, [15 min, video].

AI udfordrer uddannelse – både læring og bedømmelse må restruktureres (in Danish), edited interview from 8 March 2023 with Anders Høeg Nissen, episode 26 of podcast series Computational thinking – at tænke med maskiner, IT-Vest, published 24 April 2023, [36 min audio].

De overflødiggjorte (in Danish). 7 May 2023, long interview in Danish weekly Weekendavisen by Søren K. Villemoes. [Online] [de-overflodiggjorte-weekendavisen-7.-maj-2023].

Fremtidens intelligens – en aften om kunstig intelligens (in Danish). 16 May 2023, public conversation in the Louisiana Live series, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk. With Christiane Vejlø, moderated by Anna Ingrisch.

Artificiell intelligens och lärande (in Swedish), 23 May 2023. Presentation and panel debate. AI* Nordic AI Powwow 2023, Lund University, Sweden.

Generative AI and Higher Education, 1 June 2023, presentation and discussion to the Board of Directors of IT University of Copenhagen.

Generativ ki og højere uddannelse, 13 June 2023, presentation and discussion to the panel for Science & Engineering i uddannelserne at Akademiet for tekniske videnskaber, Denmark.

Generative KI im höheren Bildungswesen (in German), 21 June 2023, presentation and discussion at Goethe-Institut Kopenhagen, Denmark.

Her går det godt – Thore Husfeldt – AI/KI – Sommerspecial (in Danish), 28 Jul 2023. Podcast interview by Esben Bjerre and Peter Falktoft’s Her går det godt podcast, 2h21m (!). Subscription to podimo.dk required.

Generativ ki og højere uddannelse, 10 Aug 2023, keynote presentation and Q&A at Århus Statsgymnasium.

Generative AI and Higher Education, 18 Aug 2023 faculty for medicine (SUND) at Copenhagen University, COBL Summer school 2023 ([programme])

Generative AI and Higher Education, 22 Aug 2023, Fakulteten för teknik och samhälle, Malmö universitet.

Generative AI and Higher Education, 20 Sep 2023, Aftagerpanelet for institut for datalogi, IT-Universitetet i København.

Generativ ki og højere uddannelse, 23 Sep 2023, Københavns professionshøjskoles netværk for IKT og læring.

Generativ ki og højere uddannelse, 28 Sep 2023, Datamatikerlærerforeningens årsmøde.

Generativ ki og højere uddannelse, 29 Sep 2023, personale- og finansafdelingerne ved IT-Universitetet i København.

Lady Lovelace‘s objection. Keynote talk at the 2023 Annual party at IT-University of Copenhagen.

Generativ ki og højere uddannelse, 5 Oct 2023, Danske Fag-, Forsknings-, og Uddannelsesbibliotekers årsmøde. Vejle.

Generative AI and Higher Education, 10 Oct 2023, Annual meeting of Nordic Nonfiction Writers.

Generativ ki, arbejdsmarked og højere uddannelse, 23 Oct 2023, Ældre Sagen.

Generativ ki og højere uddannelse, 3 Nov 2023, Århus Katedralskole.

Generativ AI och hot mot mänskligheten, 7 Nov 2023, Sällskapet Heimdall, Malmö.

Generativ ki, ALSO Edge, 16 Nov 2023, København.

Generativ ki og højere uddannelse, 23 Nov 2023, Danske gymnasiers årsmøde, Nyborg.

Generativ ki, 30 Nov 2023, Vejle biblioteker.

Generativ ki og højere uddannelse, 6 Dec 2023, Duborg-skolen, Flensborg.

Generative AI and Higher Education, 7 Dec 2023, Precis Digital, Copenhagen.

Generativ ki og højere uddannelse, 11 Jan 2024, Børne- og undervisningsministeriet, Jørslunde konferencecenter.

Generativ ki og højere uddannelse, 26 Jan 2024, Netværksmøde for ki-assisteret uddannelse, Danmarks Akkrediteringsinstitution.

Generativ ki og højere uddannelse, 25 Jan 2024, Lyngby, 1 feb 2024, Fredericia. Faglig udvikling i praksis (»FIP-kursus«): informatik.

Generative AI and Higher Education, 2 Feb 2024, Danish Digitalization, Data Science and AI 2.0 (D3A) conference, Nyborg.

Generativ ki og højere uddannelse, Københavns Professionshøjskole Carlsberg, København.

Generativ ki og algoritmer, Netværket VL82, Lyngby.

Generativ kunstig intelligens, 29 Apr 2024 Festforelæsning for de danske Science-olympiader 2024. [1h, recording on youtube, from 10m].

Tænkende maskiner fra Ada Lovelace og Alan Turing til dagens samtalerobotter, 29 Apr 2024, Selskabet for naturlærens udbredelse, København. [1h10m, recording on youtube, Danish].

Generativ ki og højere uddannelse, 2 May 2024, SLASK Vejle.

Generative AI and Higher Education, 24 May 2024, Dansk Universitetspædagogisk Netværk-konferencen 2024 (DUNK24), Vingsted.

Generativ ki og uddannelse, 7 Jun 2024, Styrelsen for Uddannelse og Kvalitet (STUK).

Generativ ki og uddannelse, 12–14 Jun 2024, diverse optrædener under Folkemødet 2024.

Generativ kunstig intelligens, 8 Aug 2024, Vordingborg Gymnasium, Køge.

Generativ kunstig intelligens, 12 Aug 2024, Gladsaxe Gymnasium, Gladsaxe.

Generativ kunstig intelligens, 22 Aug 2024, Absalondagen, Professionshøjskolen Absalon, Slagelse.

Dannelse, teknologi og læring, 26 Sep 2024, ekspertoplæg ved Uddannelsesdebatten – Folkemødet om uddannelse, Nørre Nissum. Video of entire event at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iUwfUoKqr0s , I’m on stage at 1h and again at 2h55.

Generativ kunstig intelligens mellem menneske og maskine, 5 Nov 2024, DigiTek-dagene, Viborg Kommune.

Generative artificial intelligence and higher education, 14 Nov 2024, keynote, Institut for idræt og ernæring, Copenhagen University.

Generativ kunstig intelligens: menneske, masking, sprog og kontekst. 5 Dec 2024, Keynote, NCFF-konferencen 2024, Det nationale center for fremmedsprog. Odense.

Advisory bodies

Also since 2023 I serve on two related advisory bodies, with several internal meetings and presentations:

- Uddannelses- of Forskningsstyrelsens ekspertgruppe for kunstig intelligens, under the Danish ministry for (higher) education and research (Uddannelses- og Forskningsministeriet UFM), 2023.

- Copenhagen Business School’s AI advisory board (2023-2024).

- Fremtidens Fremmedsprogsuddannelser, national referencegruppe (2024–).

Reinforcement Learning using Human Feedback is Putting Smileys on a Shoggoth

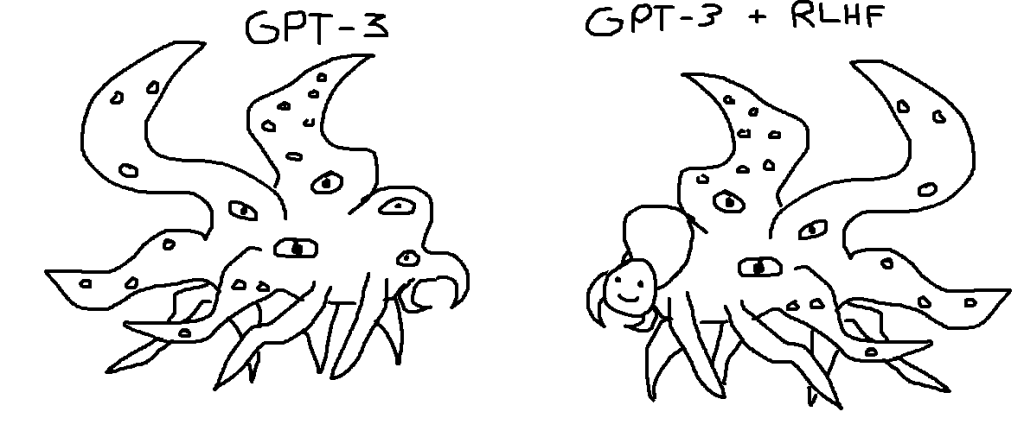

In the fictional universe of H.P. Lovecraft, a Shoggoth is one of many unfathomable horrors populating the universe. In a December 2022 tweet, Twitter user tetraspace introduced the analogy of viewing a large language model like GPT-3 as a Shoggoth, and the “friendly user interface” provided by applications such as the OpenAI chatbot ChatGPT as a smiley we put on the Shoggoth to make it understandable.

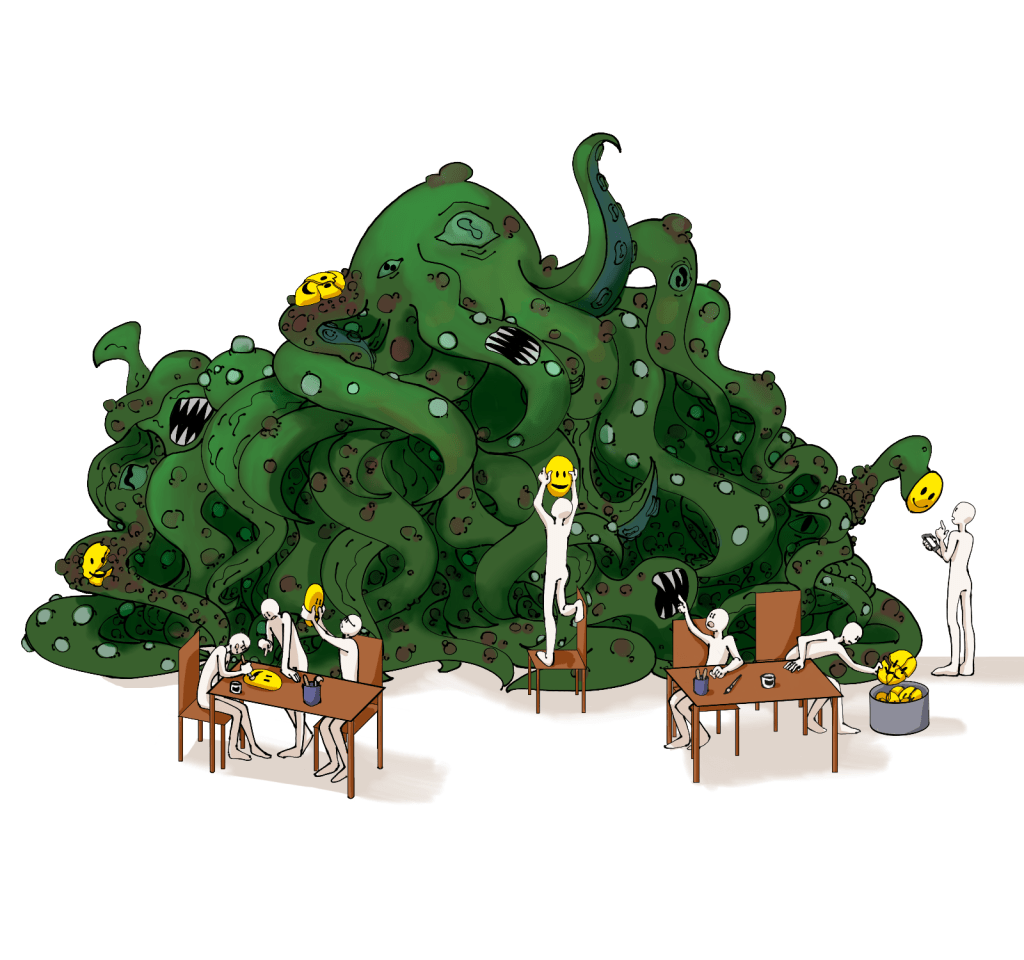

I like the analogy so much I asked my daughter to draw me a richer image that also depicts my dystopian description of the future of “basic programming”: humans busy designing new smileys to put on the eldritch Shoggoth.

Because of temporal value shift, cultural variations, and bit rot, the smiley faces need to be regularly replaced. For instance they need to relearn which topics are taboo and where, or that we’ve always been at war with Eurasia. Programmers, engineers and digital designers as worker bees in a construction site for flimsy, ephemeral masks for a demon at the Ministry of Truth. How’s what for nihilism!

Image created by Anna Husfeldt, released under CC-BY SA 3.0.

Appendix: Origins of the Shoggoth Analogy

Helen Toner in an informative 2023 Twitter thread traces back the analogy to a presentation at the machine learning conference NeurIPS 2016 by Yann LeCun:

LeChun’s analogy is Unsupervised Learning = Cake, Reinforcement Learning = Cherry on top.

Twitter user Tetraspace’s crude but seminal illustration is this:

I don’t know the original source for the more elaborate Shoggoth version that combines Tretraspace’s and LeCun’ analogies.

If you know more, tell me. Also tell me if you want me to remove these images.

Solution to STOC 2022 cryptic crossword

Across clues

- Spoke first at STOC, with handouts. (4)

SAID = S(TOC) + AID (handouts are a visual aid) - Laugh at Romanian jail without pa[r]king for Ford, say. (8)

HARRISON (Ford, an actor) = HA + R + PRISON – P (= parking) - Danes maybe cycling for cake. (7)

ECLAIR = CLAIRE (Danes, an actress) rotated = “cycling”. Difficult clue. - Squared dodecahedron contains root. (4)

EDDO (a plant). Contained in … ED DO… - With competence, like Niels Henrik? (4)

ABLY, wordplay on “like [mathematician Niels Henrik] Abel”. - Trouble sounds like beer. (3)

AIL (vb.), homophone of ALE. - L[a]nsky impales most of suricate with tip of yari. (5)

MEYER (Lansky, a mobster) = ME(Y)ER[CAT] - Taster confused desserts. (6)

TREATS = TASTER* - Programmer is a father. (3)

ADA (Lovelace) = A + DA (= father) - Some alternating state. (3)

ANY = A (as in complexity class AC) + N.Y. - Limaye without an almond, say. (3)

NUT = NUTAN – AN - Bullet point keeps her in France. (6)

PELLET = PT (= point, abbrev.) around ELLE (her, Fr.) - Assholes insert Landau symbol into abstracts after second review. (7)

EGOISTS = E (2nd letter in REVIEW) + G[O]ISTS - Logic from the Horn of Africa. (2)

SO = second order logic, also abbreviation of Somalia - Like, with probability 1. (2)

AS = like = almost surely - Complex zero first encountered by lady friend. (7)

OEDIPAL (a type of complex) = O + E + DI + PAL - Partly hesitant at ternary bit. (6)

TATTER, hidden word. - Supporting structure turns semi-liquid. (3)

GEL = LEG backward (= turned) - Everything Arthur left to end of protocol. (3)

ALL = A[rthur] + L[eft] + [protoco]L - Unbounded fan-in polylogarithmic depth circuit model is fake. (3)

ACT = AC (complexity class) + T (a Ford model) - Maybe Tracey’s luxury car runs out of [p]olynomial time. (6)

ULLMAN (an actress) = PULLMAN – P - Pin[k] dress you ordered last Friday initially returned. (5)

FLOYD (a band), backwards acrostic (“initially”, “returned”) - Relationship uncovered travel document. (2-1)

IS-A (a UML relation) = [v]ISA - Be certain about last Pfaffian orientation. (4)

BENT = BE[N]T - Detect conference cost size. (4)

FEEL = FEE + L - Matching for horses? (6)

STABLE (a type of matching, and where horses stay) - Collect information about first woman embracing the state. (8)

RETRIEVE = RE (= about) + T(he) + RI (= Rhode Island, a US state) + EVE - Central to better AI data storage technology. (4)

RAID, hidden in “…r AI d…”

Down clues

- Safer testable codes? (4, 4)

SEAT BELT = TESTABLE* (code is an iffy anagram indicator). Better clue in hindsight would have been “Locally testable codes are a buzzword. (3)” for ECO (hidden). - Maybe Arthur without Merlin is even worse … (5)

ILLER = (Arthur) MILLER – M - … definition of time than deterministic Arthur–Yaroslav. (3)

DAY = D + A +Y (a complexity class abbreviations) - Cover us about first sign of integrality gap. (6)

HIATUS = HAT + US around I(ntegrality) - Publish, but not ultimately sure about polynomial-time recurrence. (7)

RELAPSE = RELEASE – (sur)E holding P - 49 subsets the setter handles. (6)

IDEALS = stable subsets = I + DEALS - Food at indiscrete algorithms conference held around Yale’s entrance. (4)

SOYA = SODA – D (SODA without discrete) + Y - Revealed no deep confusion. (6)

OPENED = NODEEP* - Not having an arbitrary number of children. (4)

NARY = N-ARY, double definition - In Related Work section, over-inflate scientific contribution of Rabin in data structure. (4)

BRAG = R (Rabin abbreviated as in RSA) inside BAG - Iceland exists. (2)

IS, double definition - Cuckoo hashing incurs five seconds. (3)

ANI = second letters of “hAshing iNcurs fIve” - Function of what is owed, I hear. (3)

DET = homophone of “debt”. - Cut off measure of computer performance, not taking sides. (3)

LOP = [F]LOP[S] - Two sigmas above the mean, or about ten delta. (8)

TALENTED = TENDELTA* (“about” is the anagram indicator) - Coattail at breakfast? (3)

OAT, tail of COAT, a breakfast cereal. - Twisted polygon in tessellation supporting functors. (7)

TORTILE = TOR (functor) above TILE (a polygon in a tessellation). - Tree parent has two left edges. (6)

MALLEE = MA + L + L (left, twice) + E + E (edge set, twice) - Temporary visitor betrays topless arrangement. (6)

STAYER = [B]ETRAYS* - Trigonometric function is pretty dry. (3)

SEC, double definition - Denounce operator in vector analysis and put it away. (6)

DELETE = DEL + ATE (vb., past tense) - 49 litres of sick. (3)

ILL = IL (roman numerals for 49) + L - Turing machine’s second network. (4)

ALAN = A (second letter in MACHINE) + LAN - Academic degree supports unlimited games for simple minds in the US. (5)

AMEBA (US spelling of AMOEBA) = [G]AME[S] + BA - Open access journal rejected final proof in distance estimate. (4)

AFAR = AJAR – J + F (last letter of PROOF). - Conceal often sample space. (4)

LOFT, sample of “…L OFT…” - Objectively, we are American. (2)

US = objective form of “we” - It negates where you drink. (3)

BAR, double definition, the bar us used to negate a variable

Special instructions

The letters missing from 4 of the clues, indicated by […] above, are K A R P, a homophone of CARP (“sounds like nitpicking”). The answers to those clues are HARRISON, MEYER, ULLMAN, and FLOYD. The six members of the first STOC programme committee were Harrison, Meyer, Ullman, Floyd, Karp, and Hartmanis. The answer to the entire puzzle is therefore HARTMANIS, additionally indicated as “confused with H(ungarian) MARTIANS” = HMARTIANS*.

Assholes insert Landau symbol into abstracts after second review (7)

Themed cryptic crossword I compiled (over two fun evenings) for the STOC 2022 conference. Lots of short words, to make it super-friendly.

Special instructions. Four of six people that form a group related to our meeting appear in the grid, clued for their namesakes. Alas, each of these clues is missing a letter. This sound like nit-picking, but the letters form the name of the fifth person. The sixth person of the group, not to be confused with the Hungarian “Martians,” is the puzzle answer.

Across

1. Spoke first at STOC, with handouts. (4)

4. Laugh at Romanian jail without paking for Ford, say. (8)

10. Danes maybe cycling for cake. (7)

11. Squared dodecahedron contains root. (4)

12. With competence, like Niels Henrik? (4)

14. Trouble sounds like beer. (3)

16. Lnsky impales most of suricate with tip of yari. (5)

17. Taster confused desserts. (6)

19. Programmer is a father. (3)

21. Some alternating state. (3)

22. Limaye without an almond, say. (3)

23. Bullet point keeps her in France. (6)

26. Assholes insert Landau symbol into abstracts after second review. (7)

29. Logic from the Horn of Africa. (2)

31. Like, with probability 1. (2)

34. Complex zero first encountered by lady friend. (7)

38. Partly hesitant at ternary bit. (6)

39. Supporting structure turns semi-liquid. (3)

41. Everything Arthur left to end of protocol. (3)

43. Unbounded fan-in polylogarithmic depth circuit model is fake. (3)

44. Maybe Tracey’s luxury car runs out of olynomial time. (6)

45. Pin dress you ordered last Friday initially returned. (5)

46. Relationship uncovered travel document. (2-1)

47. Be certain about last Pfaffian orientation. (4)

48. Detect conference cost size. (3)

49. Matching for horses? (6)

50. Collect information about first woman embracing the state. (8)

51. Central to better AI data storage technology. (4)

Down

1. Safer testable codes? (4, 4)

2. Maybe Arthur without Merlin is even worse … (5)

3. … definition of time than deterministic Arthur–Yaroslav. (3)

4. Cover us about first sign of integrality gap. (6)

5. Publish, but not ultimately sure about polynomial-time recurrence. (7)

6. 49 subsets the setter handles. (6)

7. Food at indiscrete algorithms conference held around Yale’s entrance. (4)

8. Revealed no deep confusion. (6)

9. Not having an arbitrary number of children. (4)

13. In Related Work section, over-inflate scientific contribution of Rabin in data structure. (4)

15. Iceland exists. (2)

18. Cuckoo hashing incurs five seconds. (3)

20. Function of what is owed, I hear. (3)

24. Cut off measure of computer performance, not taking sides. (3)

25. Two sigmas above the mean, or about ten delta. (8)

27. Coattail at breakfast? (3)

28. Twisted polygon in tessellation supporting functors. (7)

30. Tree parent has two left edges. (6)

32. Temporary visitor betrays topless arrangement. (6)

33. Trigonometric function is pretty dry. (3)

35. Denounce operator in vector analysis and put it away. (6)

36. 49 litres of sick. (3)

37. Turing machine’s second network. (4)

40. Academic degree supports unlimited games for simple minds in the US. (5)

41. Open access journal rejected final proof in distance estimate. (4)

42. Conceal often sample space. (4)

44. Objectively, we are American. (2)

47. It negates where you drink. (3)

Digitisation in Higher Education

Summary of my keynote talk on 4 November 2021 at the eponymous Norwegian national conference Nasjonal konferanse: Digitalisering i høyere utdanning 2021, hosted at Bergen University and organised with the Norwegian Directorate for Higher Education and Skills. The summary is somewhat disjointed and includes some of the slides.

1. Digitisation in Higher Education (summary)

The first part of the talk is about the potential use of digital technology to improve learning outcome in specific contexts. When I gave the talk I showed a bunch of ephemeral examples that I had used myself, or which seemed otherwise cool, instructive, useful, or exciting in late 2021. These examples won’s stand the test of time, so I won’t repeat them here. A well-known and old example that everybody knows is the language learning application Duolingo.

Benefits include immediate feedback, scalability, transparency of assessment, accessibility, spaced repetition, and individual pacing or tracking of material. Common to the contexts where digital technology seems to be largely beneficial are

- learning outcomes can be validly tracked and assessed,

- it makes sense to design a clear progression or scaffolding through the curriculum,

- relevant feedback can be provided at scale and automated.

More problematic are assistive technologies, often using machine learning or other forms of decision-making processes collectively known as artificial intelligence, that ensure surface conformity of written material. These have clear benefits for authoring but also equally clear negative consequences for assessment. Modern word processors allow the production of professional-looking prose and automate surface markers of quality (layout, grammar, style, phrasing, vocabulary), which traditionally were used as proxies for content in assessment of learning outcomes; online natural language processing services like Google Translate invalidate traditional forms of language proficiency assessment based on written material. In 2021, a beta version of the programming environment GitHub Copilot automatically solves programming exercises from the task description. The same tools that perform plagiarism checks can also plagiarise very well.

So there is stuff that becomes somewhat easier by digitisation (transmission of knowledge), and where we have many ideas for what to do, and stuff that becomes much harder (valid assessment), and where we have very little idea about what to do.

A third theme is stuff that does become easier, but maybe oughtn’t. This is found under the umbrella education data mining – predicting student performance, retention, success, satisfaction, achievement, or dropout rate from harvested data such as age, gender, demographics, religion, socio-economic status, parents’ occupation, interaction with application platform, login frequency, discussion board entries, spelling mistakes, dental records, social media posts, photos, and everything else. The promise of this field—and in particular, machine-learned predictions based on polygenetic scores—is enormous; and there is an emerging literature of success stories in the educational literature. I strongly dislike this trend, but that’s just, like, my opinion.

This summaries the first part, with the foci

- what works?

- what fails?

- what should we not primarily evaluate along the works/fails axis?

There are of course a ton of other problems, which I expanded on in the full talk:

- digitisation favours certain disciplines and traditions of instruction

- it systematically undermines the authority of educators

- the intellectual property rights issues are ill understood and seem to have very little attention from educational administrators

- routine student surveillance

2. What the Hard Part Is

I’m pretty confident about part 1 (digitisation for education), and return to a confident stance in part 3 (education for digitisation). In contrast, part 2 is characterised by epistemic humility. It’s my best current shot at what makes the whole topic hard do think about.

Over the years I have learned a lot about “How to think about digitisation” from the DemTech project at IT University of Copenhagen, which looks at digitisation of democratic processes, in particular election technology. “How to digitise elections” is a priori an easier problem than “How to digitise higher education”, because the former is much more well-defined. Still, many of the same insights and phenomena apply.

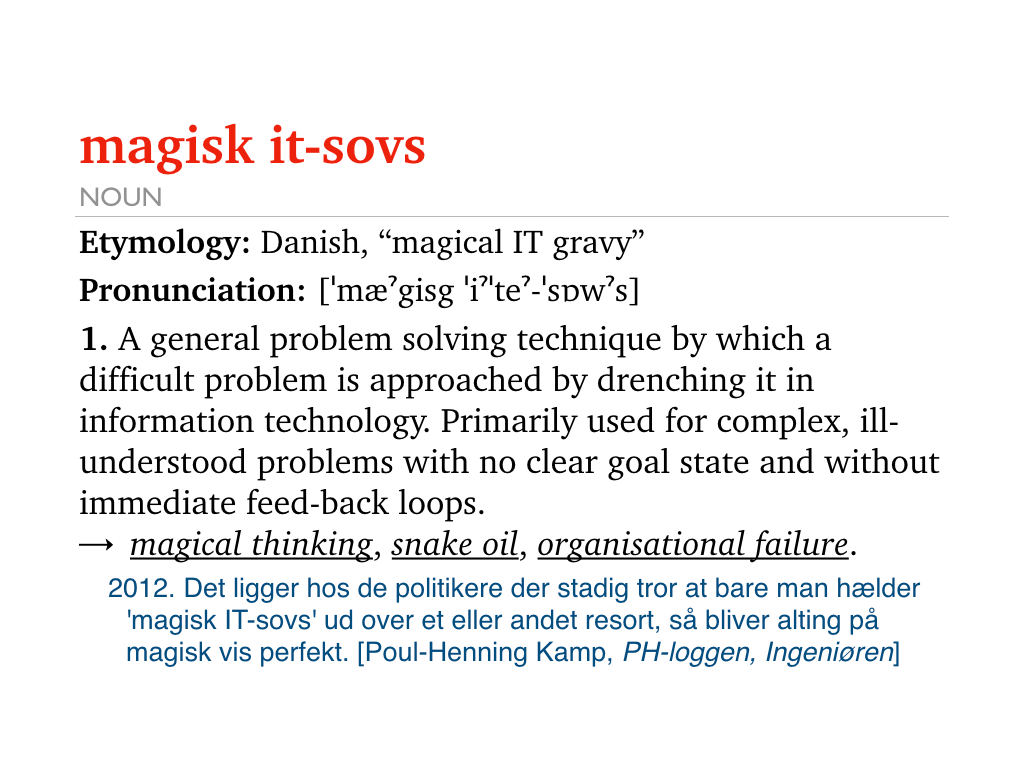

These problems include a (largely unhelpful) eagerness of various stakeholders to digitise for the sake of it. An acerbic term for this is “magical IT gravy”:

[…] politicians who still think that you can just drench a problem domain in “magical IT gravy” and then things become perfect.

Poul Henning Kamp, 2021

Briefly put, if you digitise domain X then you will digitise your description of X. (A fancy word for this is reification.) Since (for various reasons, including lack of understanding, deliberate misrepresentation, social biases, status, and political loyalty) the description of X is seldom very good, digitisation reform typically deforms X. Since digitisation is seen as adaptive within organisations, it bypasses the converstations that such transformation would normally merit.

Example: Electronic Elections

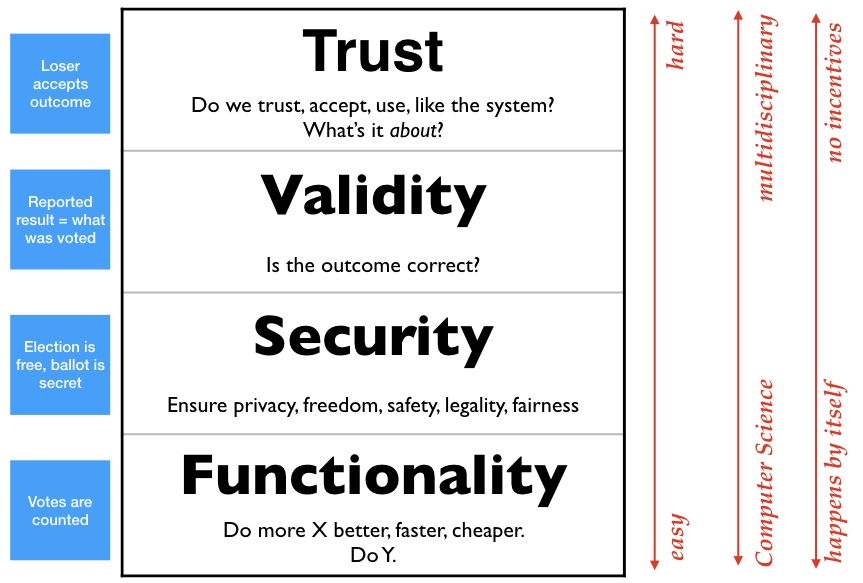

My ITU colleague Carsten Schürmann showed me this insightful taxonomy:

Let’s use voting as a concrete example to talk us through this. At the bottom is Functionality: voting is to increase a counter by 1 every time somebody casts a vote. This is easy to implement, and easy to digitise; any programmer can write an electronic voting system. Above that is Security: making sure the voting process is free (i.e., secret, private, non-coerced, universally accessible, etc.) This involves much harder computer science, for instance, cryptography. You need to have a pretty solid computer science background to get this right. Above that tier is Validity: how do we ensure that the numbers spat out by the election computer have anything to do with what people actually voted? This is even harder, in particular without allowing coercion by violating secrecy. (Google “vote selling” if you’ve never thought about this.) Finally, after thinking long and hard about all these issues (which by now include social choice theory, logic, several branches of mathematics) you arrive at what elections are actually about: Trust. The overarching goal of voting it so convince the loser that they lost. And this requires that the process is transparent.

Applications at the Functionality stage are easy (if you’re a competent programmer), they are mono-disciplinary, and the happen by themselves because geeks just want to see cool stuff work. The higher up you go in the hierarchy, the more disciplines need to be included, so the requirement for inter-disciplinary work increases. An organisational super-structure (such as a university) is needed to incentivise and coördinate the things at the top.

What is Higher Education About?

To translate the above model from voting to Higher Education, the Functionality part is transmission of knowledge: all the cool and exciting ideas I mentioned in part 1. Security corresponds to preserving privacy of learners throughout their educational history; this already conflicts with both educational tracking (e.g., for individualised progression) and reporting (e.g., for credentials). The first steps, probably in the wrong direction, can be seen by universities in Europe reacting to the European GDPR legislation, which already takes up a significant amount of organisational resources. This layer is correctly seen as annoying, depressing, time-consuming and boring, but still outshines in enthusiasm the next layer: Validity. The very features of information technology that make it incredibly useful for transmission of knowledge (speed, universality, faithful copying, depersonalised expression, accessibility, bandwidth) make it incredibly difficult to perform valid assessments, in particular in high-stakes, large-scale exams of universal skills. This is because digital technology makes it it is very easy to misrepresent authorship and originality. (Think of playing the violin, drawing, programming, parallel parking, mathematics, translating between languages—which digital artefacts would constitute proof of proficiency?)

Yet this is all still manageable, and some universities or educational systems may even choose to get this right. For instance, I think I know that to do.

But the really Hard Problem of Digitsation is the one at the top of the hierarchy: What is higher education even about?

I don’t know the answer to that.

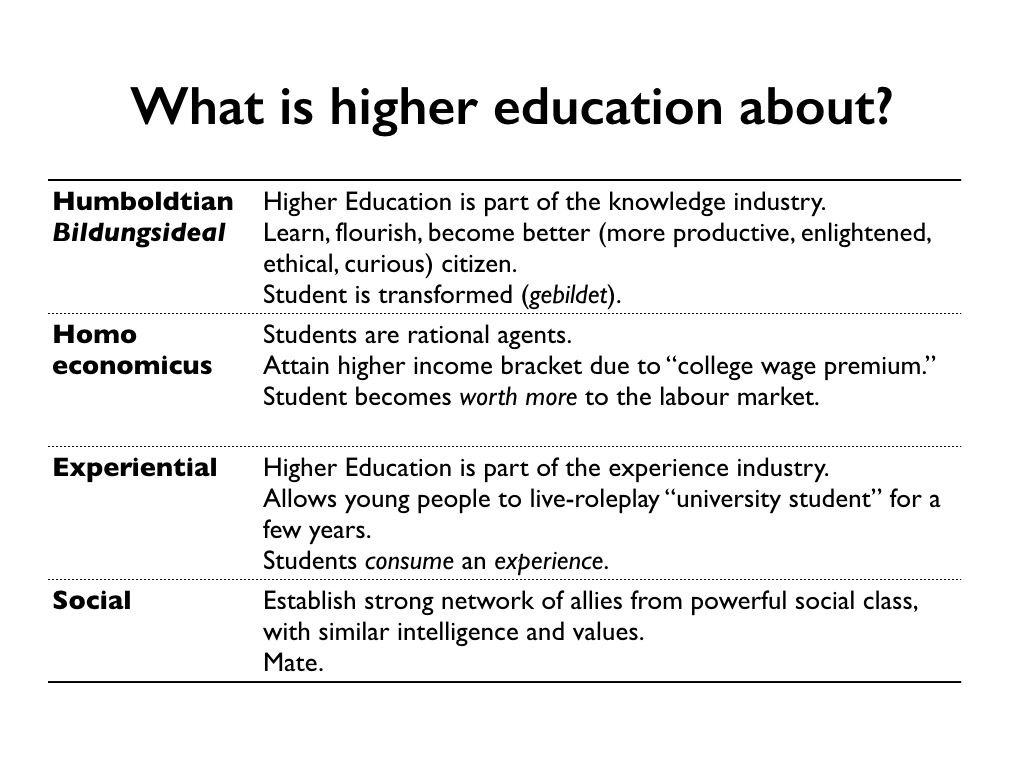

Here are some possible answers. Maybe they’re all correct:

The narrative I tell myself is very much the first one, the capital-E Enlightenment story of knowledge transmission, critical thinking, and a marketplace of ideas. We can call this the Faculty view, or Researcher’s, or Teacher’s. The Economist’s view in the 2nd row is, thankfully, largely consistent with that; it’s no mystery that the labour market in knowledge economies pays a premium for knowledgeable graduates—the two incentives are somewhat aligned. (It does, however, make a big difference in how important transmission of knowledge and validity of assessment are in relation to each other. Again, “why not both?” and there is no conflict. Critical thinking versus conformity is a much more difficult tension to resolve.)

Still, the question whether Higher Education creates human capital (such as knowledge) or selects for human capital is (and remains) very hard to talk about among educators. Very few teachers, including myself, are comfortable with the idea that education favours the ability to happily and unquestioningly perform meaningless, boring, and difficult tasks exactly like the boss/teacher wanted (but was unable/unwilling to specify honestly or clearly) in dysfunctional group, and that it selects for these traits by attrition. Mind you, it may very well be true, but let’s not digitise that. (I strongly recommend Bryan Caplan’s excellent, though-provoking, and disturbing book The Case Against Education to everybody in education.)

The two other perspectives on what Higher Education is about (Experiental, Social, both are Student perspectives) are much more difficult to align with the others. Students-as-consumers-of-an-experience (“University is Live Role Playing”) and students-as-social-primates (“University is a Meet Market”) have very different utility functions than both Faculty and Economists.

The point is: if we digitise the phenomenon of Higher Education, we need to understand what it’s about. (Or maybe what we want it to be about.) Currently, Higher Education seems to do a passable job of honouring all four explanations. I guess my position is largely consistent with Chesterton’s Fence:

In the matter of reforming things, as distinct from deforming them, there is one plain and simple principle; a principle which will probably be called a paradox. There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

G.K. Chesterton, The Thing (1929)

Even if we (as educators and educational managers) were to understand what education is about, and even if we were agree on good ideas for how to proceed, none of us lives in a world where good decisions are just made. We have to communicate with stakeholders who are themselves beholden to other stakeholders, and need to understand that these individuals live in a complicated social or organisational space where they are evaluated on their individual, institutional, or ideological loyalty. Not on the quality of their decisions.

We must expect most organisations, including most universities, to make decisions about digitisation in higher education that are based on much more important factors (to the stakeholders) than “whether it works”. Given the choice between trusting the advice of a starry-eyed snake-oil salesman (or, in our case, a magical IT gravy salesman) and a reasonable, competent, experienced, responsible, and careful teacher, most responsible organisations will choose the former.(!) The feedback loops in education are simply too long to incentivise any other behaviour.

3. Educating for Digitisation

The last part of the talk—about how to prepare higher education for digitisation—is really short. Because (I believe) I know what to do. I consider it a solved problem.

Here is the list of things to do:

- Do teach basic programming.

That’s it.

Basic programming is teachable, it is mostly learnable by the higher education target demographic, is easily diagnosed at scale, works extremely well with digitisation-as-a-tool, is extremely useful now (in 2021), applies to many domains, will likely be even more useful in future, and in more domains, is highly compatible with labour market demands, and an enabling tool in all academic disciplines.

If you’re on board with this, my best advice for anyone with the ambition to teach basic programming is to adopt the following curriculum:

- Basic programming

- Nothing else

Point 2 is really important. In particular, my advice is to not add contents like applications, history of computing, ethics, societal aspects, reflection, software design, project management, machine learning, app development, human–computer interaction, etc. Mind you, these topics are extremely interesting, and I love many of them dearly. (And they should all be taught!) But unless you are a much better teacher than me, you will not be able to make the basic programming part work.

That’s it. The full talk had better flow, included some hands-on demonstrations of cool applications, and had more jokes. I am really grateful to the organisers for giving me the chance to think somewhat coherently about these issues, and had a bunch of very fruitful and illuminating conversations with colleagues both before and after the talk. I learned a lot.

Algoritmer og informationssøgning

Presentation on 1 November 2021 at the annual meeting of the Danish Gymnasiernes, Akademiernes og Erhvervsskolernes Biblioteksforening, GAEB in Vejle, Denmark.

I had the pleasure of giving a series of lectures on algorithms for information search on the internet to the association of Danish librarians. This is a highly educated crowd with a lot of background knowledge, so we could fast-forward through some of the basic stuff.

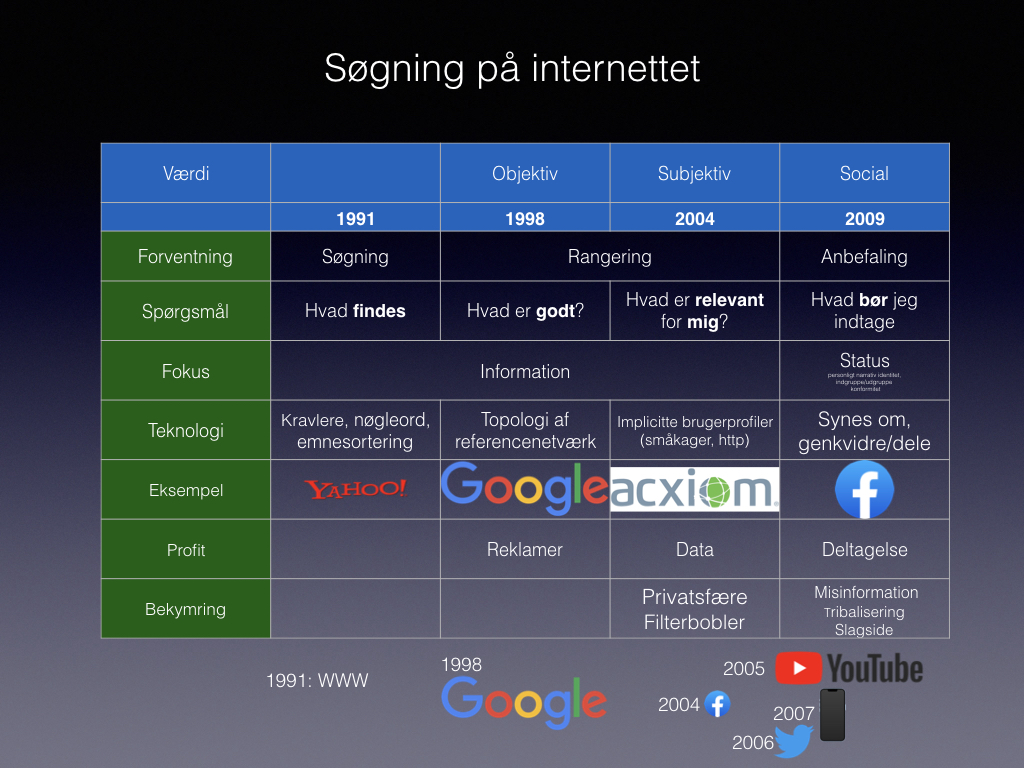

I am, however, quite happy with the historic overview slide that I created for this occasion:

Here’s an English translation:

| Objective | Subjective | Social | ||

| 1991 | 1998 | 2004 | 2009 | |

| What do we expect from the search engine? | Searching | Ranking | Ranking | Recommendation |

| What’s searching about? | Which information exists? | What has high quality? | What is relevant for me? | What ought I consume? |

| Fokus | Find information | Find information | Find information | Maintain my status, prevent or curate information |

| Core technology to be explained | Crawlers, keyword search, categories | Reference network topology | Implicit user profiles, nearest neighbour search, cookies | Like, retweet |

| Example company | Yahoo | Acxiom | Twitter, Facebook | |

| Source of profit | Advertising | User data | Attention, interaction | |

| Worry narrative | Privacy, filter bubbles | Misinformation, tribalism, bias |

Particularly cute is the row about “what is to be explained”. I’ve given talks on “how searching on the internet works” regularly since the 90s. and it’s interesting that the content and focus of what people care about and what people worry about (for various interpretations of “people”) changes so much.

- Here is the let 2000s version. How google works (in Danish). Really nice production values. I still have hair. Google is about network topology, finding stuff, and the quality measure is objectively defined by network topology and the Pagerank algorithm.

- In 2011, I was instrumental in placing the filter bubble narrative in Danish and Swedish media (Weekendavisen, Svenska dagbladet.) Suddenly it’s about subjective information targeting. I gave a lot of popular science talks about filter bubble. The algorithmic aspect is mainly about clustering.

- Today, most attention is about curation and manipulation, and the algorithmic aspect is different again.

I briefly spoke about digital education (digital dannelse), social media, and desinformation, but it’s complicated. A good part of this was informed by Hugo Mercier’s Not Born Yesterday and Jonathan Rauch’s The Constitution of Knowledge, which (I think) get this right.

The bulk of the presentation was based on somewhat tailored versions of my current Algorithms, explained talk, and an introduction to various notions of group fairness in algorithmic fairness, which can be found elsewhere in slightly different form.

There was a lot of room for audience interaction, which was really satisfying.